If you really believe in democracy, show me your media plan

Advertising doesn’t just move products. It shapes the information environment in which citizens learn, argue and vote.

On one side of the Atlantic, the White House has launched a site called Media Offenders – a government-hosted hall of shame where disfavoured outlets and journalists are paraded as liars and lunatics.

Meanwhile in France, Emmanuel Macron is arguing for something that sounds, at first glance, similar: a way to label ‘trustworthy’ media. Same grammar – lists, labels, judgements – but a very different purpose.

Where Media Offenders is designed to delegitimise, Macron’s project is meant to create a market signal for public-interest journalism – something brands and platforms could use to tell a newsroom from a rage machine. One is a blacklist. The other is closer to a procurement tool.

You wouldn’t know it from the non-French press. The row over who gets to define ‘trustworthy media’ in Europe has had barely a mention in the UK press. So this is a gap-filling exercise for marketers and planners: why this obscure French fight quietly matters to your next schedule.

News, democracy – and why it shows up on your balance sheet

Recent work by Les Relocalisateurs and the Fondation Jean-Jaurès, based on more than 10,000 respondents, maps media habits against democratic behaviour in France. In their data, 84% of regular news consumers say they vote in most elections, versus 61% of people who consume little or none. Involvement in local bodies shows a similar gap: 27% of heavy media users versus 13% of low or non-consumers.

When the authors model a France with 20 percentage points more non-consumers of media, electoral participation drops by around seven points and support for core civic values falls by about five. Their conclusion is brisk: media consumption produces democrats in much the same way school produces citizens.

A Belgian study for the ad industry reaches much the same verdict. Advertising is described as a ‘silent pillar of democratic vitality’: when budgets sustain a diverse local media mix – especially regional and local print newsbrands – turnout and cohesion rise. When spend disappears, news deserts and then democracy deserts follow. One extra local newspaper in a region is associated with roughly a 0.3-point uplift in turnout.

Meanwhile, a high-level group of economists now argues that public-interest media act like ‘central banks of the informational economy’: they stabilise the trust on which markets and governance depend, yet markets alone will not fund them adequately.

You don’t have to be sentimental about journalism to see the risk. If democracies wither where media wither, brands lose the stable, rules-based environments their business models quietly assume.

Macron’s label: a buying tool in disguise

This is the backdrop to Macron’s ‘trusted media’ label – and the choices now facing advertisers and agencies.

In meetings with regional press groups, he argued that citizens, platforms and advertisers need a way to identify outlets that meet minimum professional standards: transparent ownership, editorial independence, corrections policies, a clear line between news and opinion. He explicitly rejected any label d’État, pointing instead to profession-run schemes like RSF’s Journalism Trust Initiative – voluntary, audited and open to both national and local newsbrands.

French trade titles such as Stratégies and CB News covered it in those terms: one plank in a wider anti-disinformation package that also includes algorithm transparency and a ‘digital majority’ to protect younger users.

Then politics did what politics does. Bolloré-owned outlets portrayed the idea as a ‘Ministry of Truth’, warning that unlabelled media would be treated as second-class. The Élysée hit back, insisting that precisely because France is not an autocracy, the state cannot decide what counts as news – only independent professionals can.

Strip away the noise and what remains is something marketers say they want: a clearer, shared definition of a trustworthy news environment.

We already buy on labels – viewability, fraud, carbon. A credible trust label would simply tell you whether an outlet behaves like a newsroom at all. For print and digital newsbrands that still employ reporters and editors, especially regional titles, that is less a threat than a spotlight.

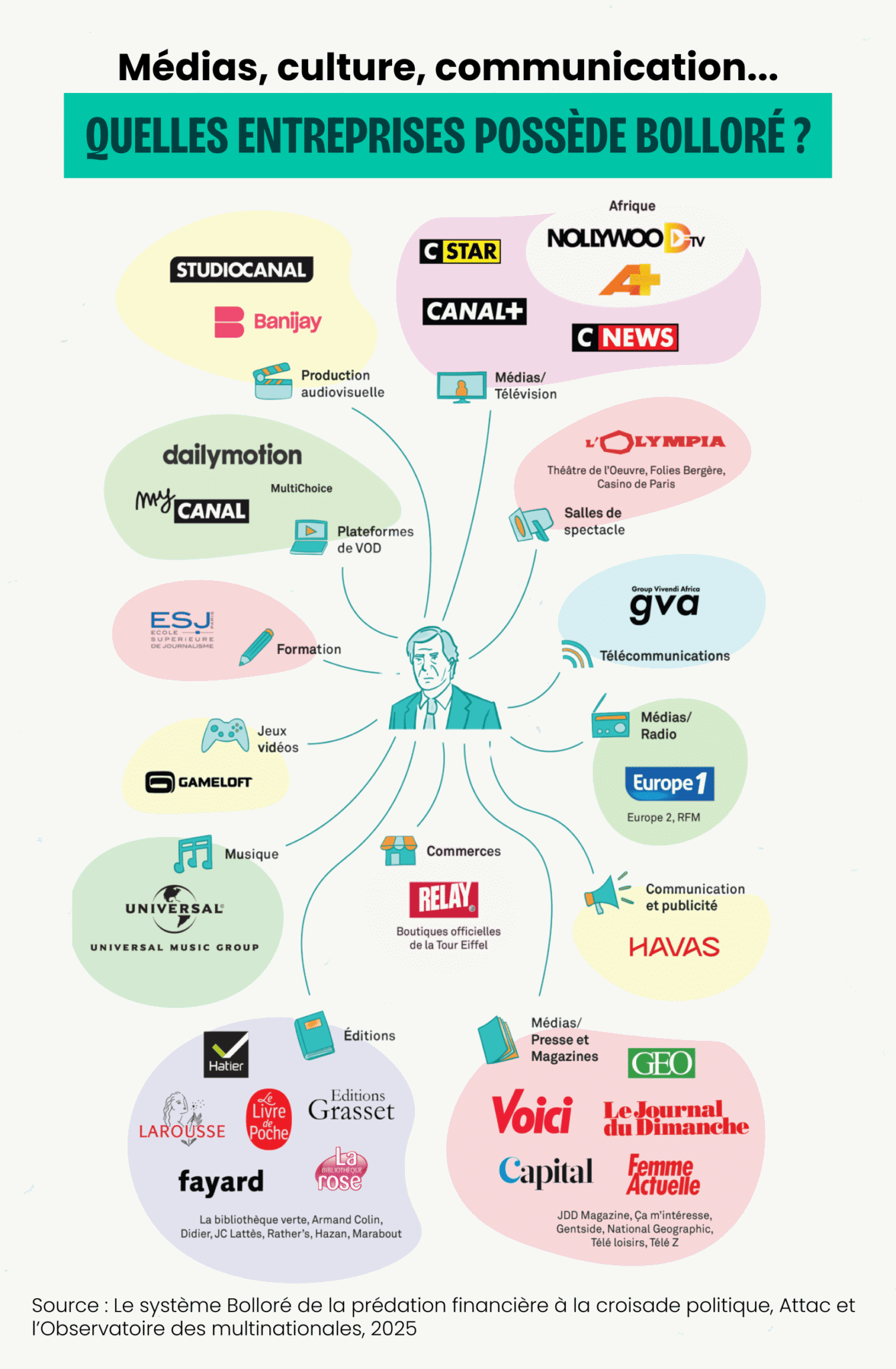

The Bolloré ecosystem: shortcut and minefield

In France, the “Bolloré ecosystem” is both a convenient media-buying shortcut and a political, brand-safety minefield. Unlike the UK (press oligopolies) or Spain and Germany (TV duopolies), France has drifted towards a single cross-media pole in which broadcasters, publishers and an agency network sit in the same orbit.

Whatever the corporate wrappers, the point for advertisers is simple: one centre of influence can sit across attention, narrative and spend.

That influence is not confined to television. Yes, CNews runs a Fox-style schedule heavy on commentary while licensed as “news” – and it is under scrutiny after the Conseil d’État told the regulator to re-examine whether it still meets obligations on pluralism and independence. But the attachment underlines the wider play: after Bolloré’s grip tightened on Hachette, the push moved into publishing. Fayard has signed high-profile right and far-right figures, prompting internal warnings and departures, while the group’s distribution power helps turn books into national talking points.

For brands, the risk is not just adjacency to provocative content. It is the perception of funding an ecosystem designed to shape public opinion.

In that context, a profession-run trust label is not doctrinal hair-splitting. It is a practical counterweight: a way for advertisers and agencies to back outlets – including regional papers and local broadcasters – that behave like “central banks of trust”, rather than volatility machines.

So what, exactly, should brands do?

For agencies and marketers, the implications are less about taking sides in French politics and more about cleaning up the logic of their own plans.

- Treat news – including print – as infrastructure, not just adjacency risk. Deliberately allocate a share of spend, national and local, to public-interest newsbrands: quality national titles, regional press, broadcaster-linked news sites. Not as CSR, but because the evidence says societies – and markets – function better when those brands are strong.

- Use trust signals when they exist. If JTI or similar standards are available in a market, add them to your RFPs and inclusion lists in the same breath as viewability and fraud. Where labels do not yet exist, ask newsbrands for the basics: governance, editorial codes, corrections. If an outlet cannot answer, that is a signal too.

- Remember this isn’t just about democracy – it’s about effectiveness. Bodies like Newsworks in the UK, and their equivalents elsewhere, have shown repeatedly that advertising in trusted news environments delivers stronger business outcomes: higher attention, better long-term brand effects, more efficient activation. In other words, the channels that keep citizens informed also tend to keep media money working harder.

- Recognise that this fight over who defines ‘trustworthy media’ in Europe is under-reported outside of France, but not irrelevant to European budgets. If European democracies continue to trade newsbrands for newsfeeds, and let media deserts, rage channels and government enemies lists fill the gap, brands will feel it where it hurts: in boycotts, regulatory shocks and a degree of unpredictability no media plan can smooth out.

Advertising doesn’t just move products. It funds the information environment in which citizens decide what, and whom, to believe.

If brands genuinely care about trust – and performance – it’s time their media plans started acting like it.