Billions lost to dull ads: why print may be the overlooked winner in the attention economy

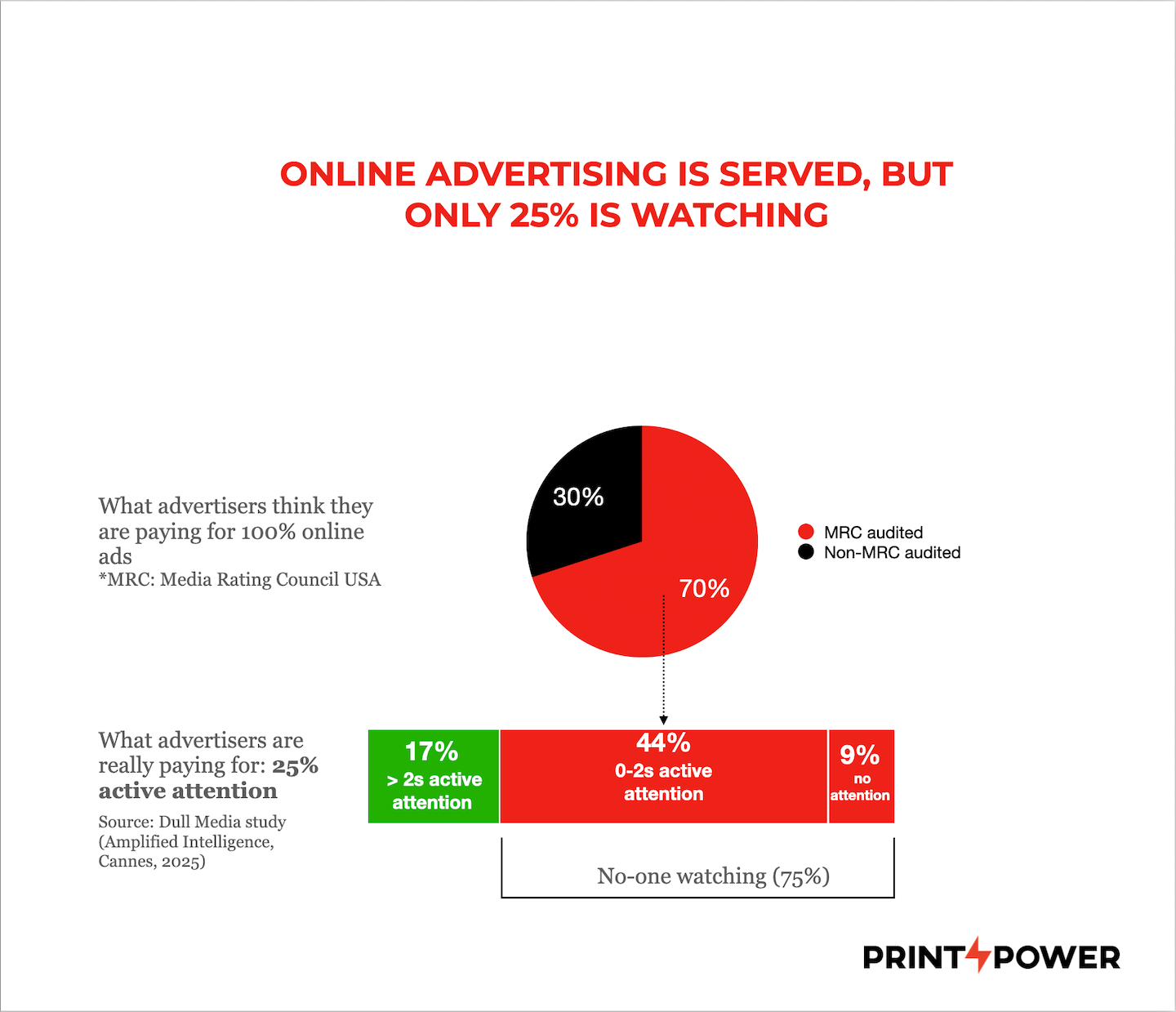

Advertisers are throwing away billions of dollars every year on advertising that either fails to engage consumers emotionally or is delivered in media environments where it is barely noticed. That is the conclusion of two sets of research presented at successive Cannes Lions festivals, which together shed light on a growing crisis in marketing efficiency.

In 2024, Peter Field and Adam Morgan, working with the research agency System1, warned that the financial penalty for running dull creative was staggering. A year later, Dr Karen Nelson-Field of Amplified Intelligence extended the argument to the media landscape itself, showing that a majority of digital inventory attracts little or no active attention.

New evidence from Lumen Research adds a further twist: when print advertising data are mapped onto Nelson-Field’s framework, it emerges as a medium that consistently escapes the worst of this “dull media tax”. In a market dominated by low-attention digital formats, print appears to deliver efficient and reliable returns — raising uncomfortable questions about how marketers allocate their budgets.

The high price of dull creative

At Cannes 2024, Field and Morgan presented an analysis combining decades of IPA effectiveness data with System1’s extensive database of ad testing results. Their conclusion was blunt: dull creative can work, but only if supported with dramatically more spending.

In the UK, they calculated, a bland television campaign needs around £10m in extra budget each year to achieve the same level of effectiveness as a creative one. In the US, the price tag rises to $189bn annually.

In other words, campaigns that fail to move audiences emotionally are not just artistically uninspiring, they are financially ruinous. Brands pay heavily for the privilege of being ignored.

The cost of dull media

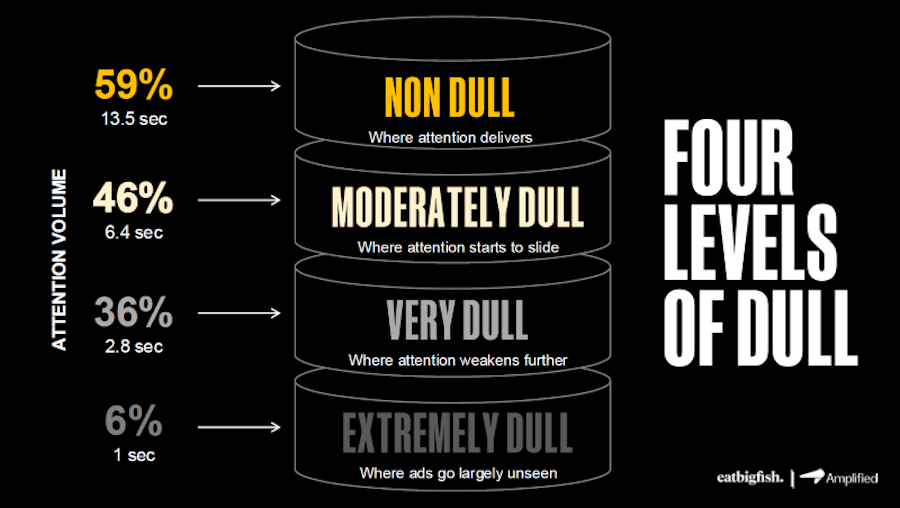

If Field and Morgan focused on what happens when creative fails, Nelson-Field turned the spotlight onto the platforms themselves. Her Dull Media study (Cannes 2025) introduced a new measure, Attention Volume (AV), defined as the product of attentive reach, active attention time and time-in-view. Importantly, Amplified set a 2-second threshold before attention is counted as active, making it a stringent test.

Formats were ranked into quartiles:

Non-Dull: ≈59% AV, ~13.5s active attention

Moderately Dull: ≈46% AV, ~6.4s active attention

Very Dull: ≈36% AV, ~2.8s active attention

Extremely Dull: ≈6% AV, ~1s active attention

The findings were damning. Across audited US digital inventory, 75% received zero active attention. For advertisers, that equates to wasting 43 cents for every advertising dollar. In total, Nelson-Field estimated, the “dull media tax” drains nearly $200bn a year from global budgets.

This financial erosion is visible in ROI terms. Amplified’s modelling shows that long-term returns fall steadily as attention declines: from $5.21 ROI per $1 spent in the Non-Dull tier, down to $4.48 in the Extremely Dull tier.

The research also sheds light on a long-running debate: what matters more, creative or media? The results suggest the medium contributes 65–70% of performance outcome, while creative accounts for only 30–35%. The implication is stark: even the best creative will fail if placed in the wrong media environment.

Where print fits in

The Dull Media study did not include print, so no formal quartile assignment is possible. To gauge print’s position in the attention economy, we turn to Lumen Research, which reports attentive seconds per 1,000 impressions (APM) using a ≥1-second threshold.

Recent cross-media benchmarks indicate:

TV 30″ non-skippable ≈ 6,439 attentive seconds

YouTube ≈ 3,377s

Out-of-home posters ≈ 1,610s

Press (print) ≈ 1,594s

Facebook ≈ 804s

Instagram ≈ 707s

Display banners ≈ 490s

On this measure, print sits in the mid-range of attention supply: not at the level of premium video, but decisively ahead of banners and much social inventory. Print also shows very high view rates (70–90%) and page dwell times of 2–3.5 seconds—conditions that are far from the low-attention profile highlighted in Amplified’s bottom tier (≈1s active attention with high non-attention).

Because Amplified did not test print, we do not assign a quartile or a precise long-term ROI tier to print within that framework. The cautious inference, using Lumen’s attention supply and Amplified’s ROI gradient (from $5.21 in the top tier to $4.48 in the bottom), is that print avoids the steepest ROI penalty associated with the lowest-attention formats, while exact placement on Amplified’s scale remains undetermined.

Why print matters in the attention economy

This reframing has significant implications for print. Long dismissed as a legacy medium, print advertising demonstrates qualities that align well with the new attention-based logic.

* High visibility: Print ads are seen by 70–90% of readers, compared with single-digit percentages for much online inventory. For marketers, the gulf in readership rates between print and digital is striking.

* Stronger conditions for memory: With dwell times of 2–3.5 seconds, print pages remain open long enough to create more favourable conditions for building memory than many digital formats. While active attention data for print are not yet published, its higher dwell time and view rates suggest it is far more likely to be processed than fleeting digital impressions.

* Efficiency: In Lumen’s framework, print delivers 1,594 attentive seconds per 1,000 impressions — positioning it alongside out-of-home posters and far above banners and social media.

Financially, this places print outside the danger zone of “extremely dull” media and into territory where advertising continues to generate positive brand returns.

Voices from the industry

Staffan Hultén, CEO of RAM, argues that the future lies in combining channels rather than treating them as rivals: “The future is not binary, it is hybrid. Digital advertising has its place, but it is not the solution to everything. A print ad can create a tactile anchor. An event experience can deepen the brand relationship. A digital campaign can reinforce both.”

Ian Gibbs of DMA UK highlights how attention is becoming embedded in practice: “At the DMA Awards, 27% of entries now mention attention.” Importantly, these are direct marketing cases, showing that the concept is expanding beyond big-brand media into one-to-one channels.

Mike Follett of Lumen added a further perspective at Mad//Fest: “Attention is more than meets the eyes — it also includes taste, haptic and audio.” As a medium, print embodies this multi-sensory quality, combining visual and tactile cues, and sometimes even auditory ones — making it a stronger competitor than formats relying only on fleeting screen views.

The broader implications

For marketers, the combined message of these studies is sobering. Creative that fails to engage and media that fail to attract attention are not neutral — they actively destroy value. Field and Morgan put the creative cost at $189bn annually in the US alone. Nelson-Field estimates the dull media tax at around $200bn worldwide.

Against this backdrop, print looks less like an anachronism and more like a safe investment. It may not rival premium video for impact, but it consistently avoids the traps of low attention and poor ROI that plague so much digital spend.

Towards a better balance

Advertising has always reinvented its metrics: ratings in the 1950s, clicks in the 1990s, viewability in the 2010s. Today, the evidence is mounting that the next currency is attention.

In this context, print has a strong case to make. It commands dwell time, achieves high view rates, and sits in the ROI-positive zone when mapped against the toughest attention benchmarks.

For brands, that means reconsidering the role of print in the media mix. For publishers and printers, it means articulating value not in terms of nostalgia, but in the hard currency of attentive seconds and ROI.

Advertising has always been about winning a share of mind. As the attention economy takes shape, print’s ability to command time, focus and memory may prove to be its quiet but enduring strength.